Owen Lynch likes to keep to himself, even when he's playing a video game against 100 other players. His survival strategy in games is much like his strategy in life -- avoid other people.

"Yeah, there's a theme," he said, joking about his behavior.

Editors Note: Some of the documents linked in this report contain terms that readers may find offensive.

Owen has autism, and that can make it hard for him to socialize. For as long as he can remember, he said, his social problems have made him a target for bullies. The bullying came to a head about a week after the school shootings in Parkland, Florida, earlier this year. Some of his fellow students at Norwalk High School targeted him on social media, saying that he’d be the next school shooter.

“I haven't really been getting a lot of sleep lately,” Owen said, speaking to Connecticut Public Radio in March. “I've been kind of stressed out during nights, having panic attacks."

Ultimately one of his classmates called police, and reported that another student might have a gun in the building.

The officers pulled several students from class to search them and ask them questions. When police came to Owen’s room, he noticed his classmates staring at him.

"And I was like, 'Oh, they're here for me’,” Owen said. “‘This is not gonna be nice.' And at that moment I knew that at least half the school was going to say something about me."

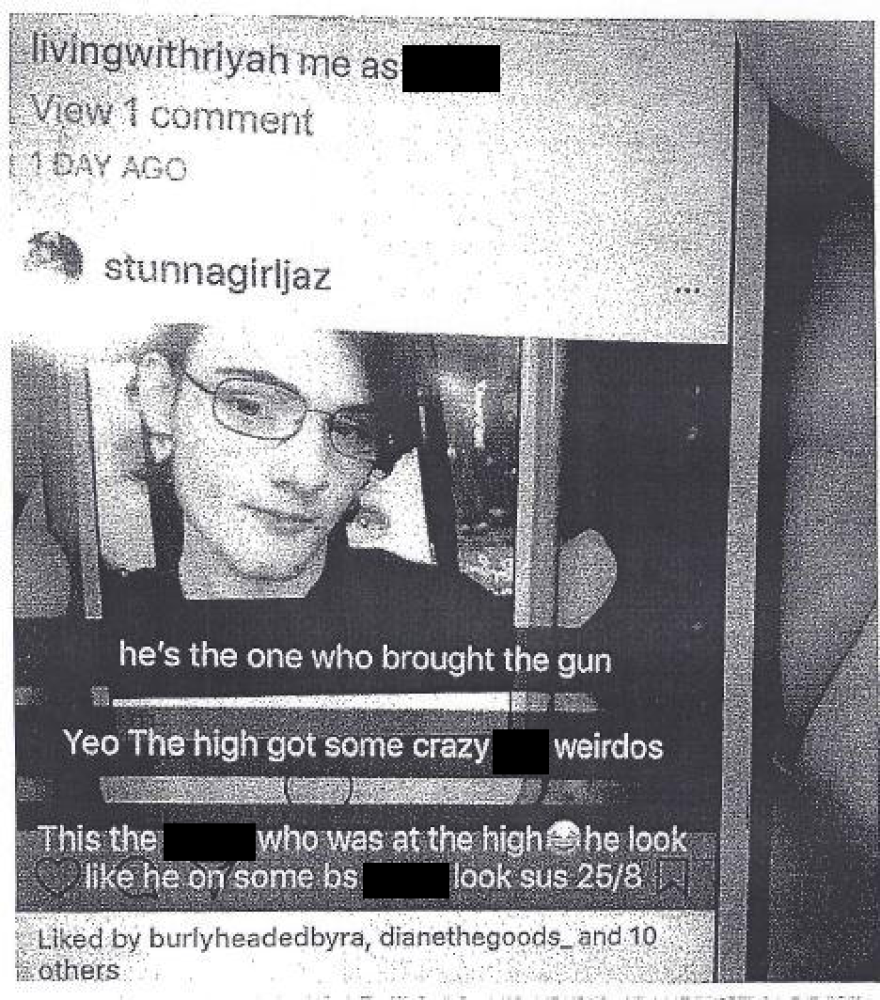

He was right. Police concluded it was a false alarm, and found nothing on Owen or anyone else. But other students quickly took to social media and sent him messages. One student shared a photo of Owen’s face on a stick figure holding a gun, and others wrote about him with the hashtag “school shooter.”

So Owen hasn't stepped foot in the school since. His mom, Heather Florian, said his decision to stay home has deep roots.

"Owen doesn't feel safe going back there,” Florian said. “This isn't a singular incident of bullying, this is a long history of bullying Owen."

Despite repeated attempts, school officials declined to be interviewed on Owen's history and the bullying incident, citing student privacy concerns. The school declined to provide Owen’s records, despite his mother giving them permission. Florian provided her son’s educational and medical records for this story.

When Owen was 10, a psychologist diagnosed him PDD NOS, which is an autism spectrum disorder. Records show that the Norwalk school district acknowledged that Owen had “heightened levels of depression… learning atypically, and withdrawal, with lower adaptive skills,” but that it was unlikely he had autism and he was “not eligible for special education services.”

Years went by and he wasn’t getting any special education. Meanwhile, educational records provided by Owen’s mother show the bullying continued. When he was 13, a district report noted that "Owen has complained of being bullied last year during his walk home," and a medical record indicated that other students had thrown rocks at him.

In middle school, the bullying got so bad that he had to go to the hospital -- three times, for depression, and feeling suicidal.

"During one of his hospitalizations at Yale, he was diagnosed with PTSD, due to bullying,” Florian said.

Not long after that, he was suspended from middle school. The details of what happened are disputed, and school records don’t include any information aside from his suspension being related to “threatening.” According to one account, some students claimed that Owen said he would blow up the school. Police got involved, and he had to go to court, but the judge threw out the charges. Owen and his mother said the whole thing was a misunderstanding.

Court records for dismissed cases in Connecticut are expunged soon after a judge’s decision.

Owen finished out that year at a specialized private school for students with emotional problems. He later returned to Norwalk Public Schools, but the bullying continued, which led to more emotional problems.

Here's what's at issue in this case. The district cites Owen’s emotional problems as his primary disability, whereas autism experts would counter that his emotional problems are in fact a symptom of his autism and a consequence of being bullied.

To complicate matters even further, records show that school officials do recognize his autism diagnosis, but they don’t identify it as a disability under which he should receive services.

“It’s offensive when they don’t accept a diagnosis and they want to just label him a problem,” Florian said.

Even though school documents indicate Owen has been consistently bullied over the years, the district has since reported that the bullying didn’t happen. After he was called a school shooter, a district investigation -- completed by a social worker who years prior had written about Owen’s bullying concerns -- found “the allegation of a history of bullying… is not verified.”

But that same investigation included this advice for Owen -- they wanted to help him “ignore the bullying.”

Below is a section of a medical discharge summary by Four Winds Hospital, provided to Connecticut Public Radio by an advocate for the Florian family. This is from 2014. The second frame is a section of the 2018 investigation by Norwalk social worker Rondi Olson into the bullying incident, which refutes the medical record. The last frame is another section of Olson's report, with suggested next steps.

For Florian, it’s a triple-whammy -- the district didn’t give him services related to his autism. Instead, they treated his emotional problems which were partially the result of him being bullied. At the same time, the district ignored his history of being bullied

When kids said that Owen would be the next school shooter, there was a heightened sense of awareness because of the recent shootings in Parkland, Florida. That created a perfect storm, of sorts, to single out Owen, whose social and emotional problems were now being seen by some classmates as threatening behavior.

However, researchers suggest that the link between autism and violence has long been debunked.

“There is no evidence base that suggests that individuals with autism are actually more at risk for becoming school shooters,” said Hank Schwartz, a psychiatrist at the Institute of Living in Hartford, one of the oldest mental health hospitals in the country. He said students with autism often act and talk differently, and their peers can sometimes misinterpret those messages.

“Because they act in a withdrawn way, and at times may have some difficulty with their connectedness to others -- such individuals become the subject of bullying and of suspicion, and it's quite unfortunate,” Schwartz said.

However, being bullied and having a history of mental illness -- both relevant in Owen’s case -- are risk factors for becoming violent. The district, though, has done little to address either, Florian said. Documents show Owen has no history of violent behavior.

A school’s role in preventing potentially violent acts is key, according to Connecticut’s investigation into Adam Lanza’s murderous rampage at Sandy Hook Elementary back in 2012. Investigators found the school district had consistently failed to educate Lanza, and while they avoided saying it played any direct role in his mental decline, advocates have pointed to these failures as a likely and perhaps significant contributor.

“Appropriate, multidisciplinary and expert treatment, integrated into the family setting, community, and school might have prevented the later deterioration in [Lanza’s] mental state,” investigators from the state’s Office of the Child Advocate wrote. “The lack of sustained, expert-driven and well-coordinated mental health treatment, and medical and educational planning ultimately enabled his progressive deterioration.”

While she wouldn’t comment on Owen Lynch’s case or Norwalk’s history, Fran Rabinowitz, executive director of the Connecticut Association of Public School Superintendents, said that providing appropriate services to students can be complicated when parents and schools disagree over what to do.

“It’s all about building that relationship on both sides,” she said. “It’s about establishing trust and respect on both sides. And if it’s not there -- you’ve got to persist in a relationship to build it.”

The incident with Owen represents a confluence of factors that his mother said could have been avoided had the district recognized his autism diagnosis and the bullying much earlier. Once Owen became known as the kid who threatened to blow up the school, it wasn’t a big leap to call him the kid who would shoot up the school.

“I just want what’s best for Owen, and I just, I’m tired of fighting for it on my own,” she said. “It’s a hard fight.”

In a statement, Yvette Goorevitch, chief of specialized learning and student services for Norwalk schools, said she understood that students with disabilities are “particularly vulnerable” to cyberbullying.

“We take this issue seriously and we are committed to safe, secure and inclusive schools where all truly means all,” Goorevitch wrote.

Norwalk's special education department has been the subject of three separate state investigations since 2008 that found significant problems with how the program is managed. The district has gone through numerous department leaders during that time.

Owen didn’t attend school for the rest of the semester. He only got a few hours of tutoring each week. The family has now moved to Seymour, where he’s attending school this year. Owen’s situation is part of the reason for the move.