Efforts to ban books have surged across the country, and Connecticut is no exception.

In 2022, there were 29 library title challenges in the state, according to the American Library Association. That number more than quadrupled the following year, reaching 117 in 2023.

The Accountability Project paired up with Connecticut Public state government reporter Michayla Savitt to explore the topic.

We interviewed librarians, parents and state lawmakers, and sifted through hundreds of school board meeting minutes.

We found books that spark controversy in Connecticut are often intended for young readers, and discuss themes of gender identity, sexual orientation, sexual education, race and racism.

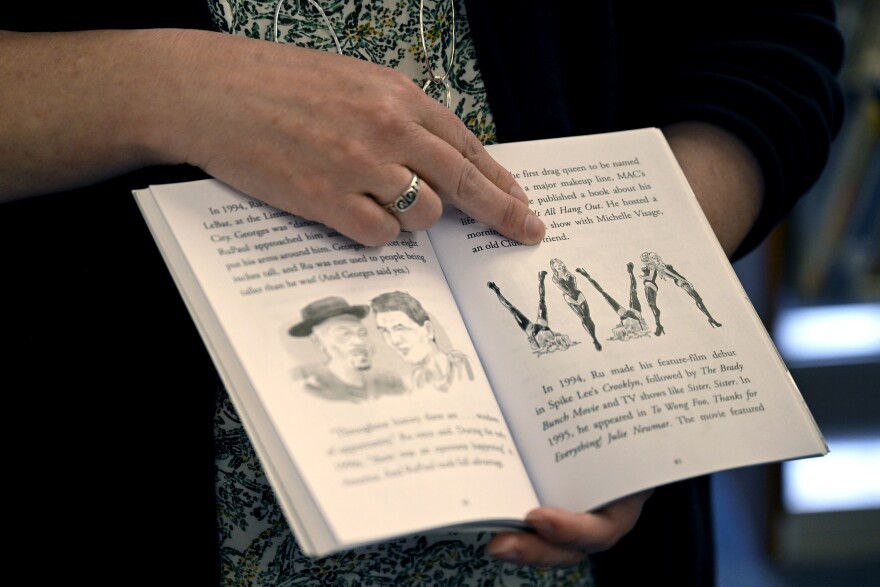

In one example, at the Cragin Memorial Library in Colchester, a patron filed a petition in 2022 against the book “Who is RuPaul?”, which was on display for Pride Month, a celebration of the impact lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people have had in the United States and beyond. The book is part of a popular children’s biography series meant for kids ages 9 to 12.

The book was eventually put back on the shelves. But similar challenges have become more frequent, and the process of evaluating literature differs from one community to the next.

In response, Connecticut lawmakers have explored creating a more uniform approach. One bill, which is in committee, would immunize librarians from civil and criminal liability stemming from challenges to library materials.

Another bill would require all libraries to create a process to handle book petitions or challenges. Under the measure, a title couldn’t be removed solely because someone finds it offensive. Books would also be protected from additional challenges for three years if an attempt to have them removed fails.

Senate Majority Leader Bob Duff, a Norwalk Democrat, helped introduce that measure. The legislation might make it easier to track exactly how many books are being challenged in the state.

State Republicans have proposed other provisions, saying minors shouldn’t be able to access materials that have sexually explicit content or nudity.

“We’re not trying to ban books,” state Sen. Henri Martin, a Bristol Republican, said in an exchange at a February public hearing. “What we’re trying to do is protect our children.”

The American Library Association, a nonprofit that promotes libraries and library education, tracks efforts to ban or restrict access to reading materials nationally. To collect that information, it relies on news stories and reports from individual librarians.

That means some attempts to take books off the shelves can be missed.

Some librarians won’t report book bans out of fear, said Jenny Lussier, president of the Connecticut Association of School Librarians. Some school librarians in Connecticut have received threats for doing so, she added.

“We’re all professionals,” Lussier said. “We all want what’s best for our kids.”