Ari Shapiro has traveled the world, both as a journalist for NPR and as a singer with the music group Pink Martini. He also occasionally performs in a cabaret act with actor Alan Cumming. No matter where he is, Shapiro says he always brings his "full self" — albeit maybe a "slightly different iteration" depending on the audience.

"When I'm in the fields for NPR stories, or when I'm hosting All Things Considered, ... I don't want to disappear, but I want to be a surrogate for the listener," Shapiro says. "I want to make the listener feel like they could be where I am, like they could be in my shoes."

Performing cabaret or singing on stage with Pink Martini is a different story. That's when Shapiro feels more comfortable inhabiting the spotlight: "I can be camp. I can be gay. I can make Jewish jokes. I can sort of toy with my identity as a vehicle for connection, which is less foregrounded when I'm on NPR."

Shapiro's path to NPR host was a winding one. In college, he applied for an NPR internship — and was turned down. He's able to laugh about it now. "Anybody who ever feels like they're a failure, just remember: NPR's Ari Shapiro got rejected for an NPR internship," he says.

Shapiro did eventually land an internship with the network, where he wound up working with legal affairs correspondent Nina Totenberg. He went on to other NPR roles, first as an editorial assistant on Morning Edition, then as a Justice Department reporter, a White House correspondent, London bureau chief and a foreign correspondent. He became a host on All Things Considered in 2015.

Shapiro says as an interviewer, it's important to listen and respond to what a guest is saying. When asking questions, he tries to avoid framing things in terms of superlatives.

"If you ask me to choose the best interview that I ever did, I will be paralyzed," he says. "But if you ask me to tell you about an especially memorable interview that I did in the last month or an especially rewarding interview that I did overseas, then I've got a million to choose from and I can tell you stories all day."

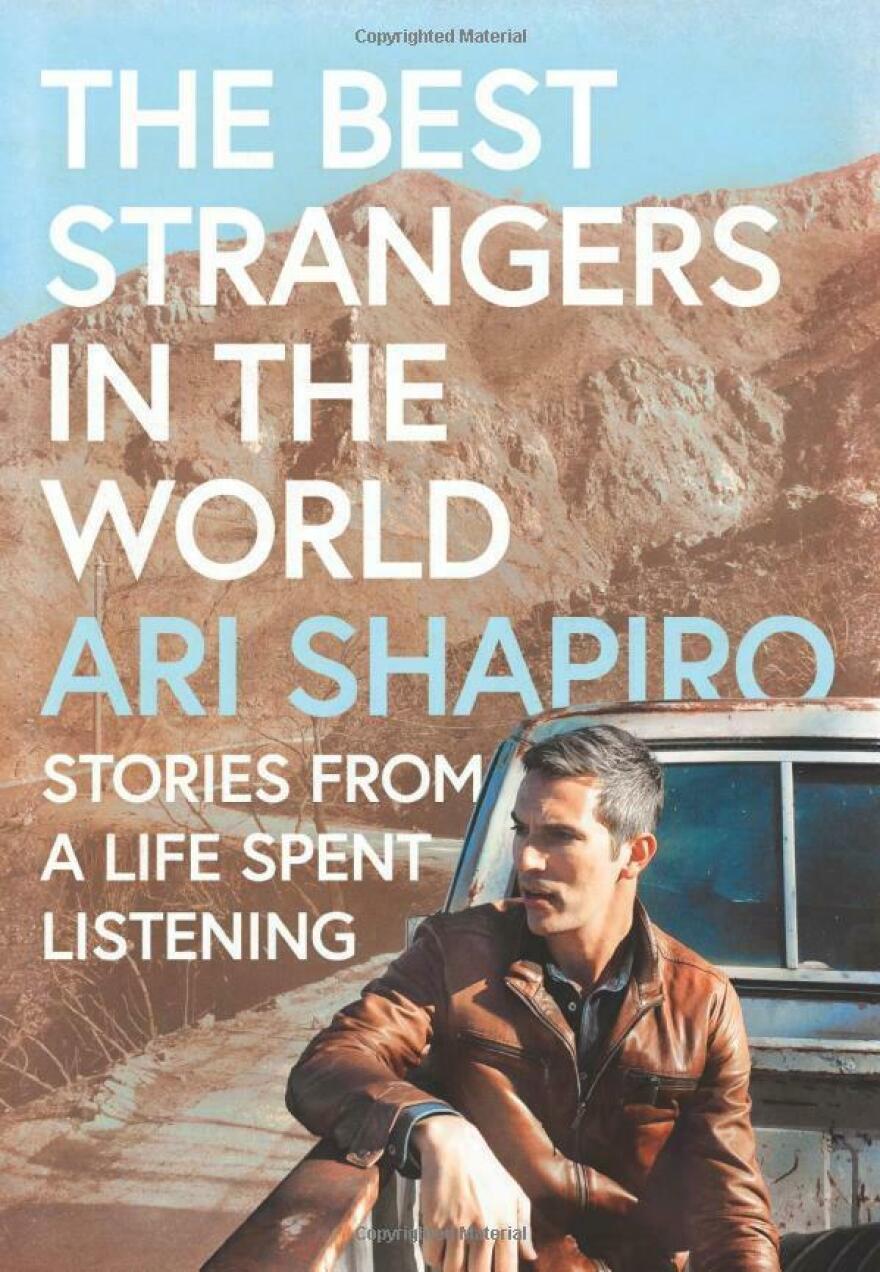

Shapiro shares some of his own most memorable stories in his new memoir, The Best Strangers in the World: Stories from a Life Spent Listening.

Interview highlights

On becoming friends with — and joining — Pink Martini

After I became friends with them, anytime the band would pass through Washington, D.C., on tour, I would throw a brunch, a dinner, cocktails, barbecue, something I would have them over. And in about 2008, there was a dinner cookout that sort of turned into a late-night singalong around my piano. ... It was sort of late into the night we were all singing together. And the next morning, Thomas Lauderdale, the pianist who is also Pink Martini's bandleader, said, "Hey, we're writing this song for the next album that we want a man to sing. Why don't you come to Portland and record it for us on the album?" Which to me was such a surreal out-of-body experience to be asked to sing with this band that I had loved since I was in high school. I never thought it would actually happen. And of course, I immediately said yes. ...

The first time I ever sang with any band live on stage anywhere was in front of 18,000 people.

And then I was in Portland recording with the band, terrified, so not confident in my ability. I'm sure that it would never actually make it onto the album. And then it did. And then Thomas said, "Well, we need to find a time for you to perform this live with us. So why don't you come to the Hollywood Bowl?" And so the first time I ever sang with any band live on stage anywhere was in front of 18,000 people.

On what it's like to perform on stage

There is such a rush of being on stage in front of a crowd and knowing in that moment that either you've got them in the palm of your hand, or you don't and you have to get them back. ... I feel like energy, like electricity, is coming through my feet and my hands. And I'm sharing that with the audience and I feel them giving it back to me. And it is like I feel almost like a conduit for something.

On introducing himself on stage to people who recognize his voice from NPR

When I do a live performance, I often, but not always, I'll come out, I'll sing a song or whatever, and then I'll say, "From the Hollywood Bowl, this is Pink Martini. I'm Ari Shapiro," which gets a laugh because people recognize that voice, that cadence, and then I pause and I say, "And you look nothing like what I imagined either," which I think is a way of not only breaking the ice, but also saying this is going to be a slightly different iteration of me than you might be accustomed to hearing on NPR.

On advice he got from Nina Totenberg when he interned for her

The most vivid advice I remember is she heard me on the phone next to her and we shared a cubicle and I was requesting an interview with somebody. And I was sort of "I wonder... Would you consider... Maybe... Possibly." And Nina shouted, "Ari, grow a pair!" She was like, "You need to ask for what you want directly and firmly, and don't take no for an answer." That's Nina. ...

I've learned so much from Nina. I remember after she would do an interview, I would transcribe it. This is before there were auto-transcription services. And in transcribing it, I would think carefully about when and where she asked the questions. When she asked a follow-up, when she moved on, how she framed her questions. I learned so much because I hadn't written for the school newspaper. I hadn't taken a journalism course. Interning at NPR really was how I learned journalism.

On finding his "NPR voice"

I knew I could never sound like Robert Siegel or Bob Edwards, who were like the two authoritative, stentorian voices of NPR. I wasn't consciously trying to do this, but I think I was aspiring to kind of like the warmth of Susan Stamberg, hopefully, and maybe the inquisitiveness of Jacki Lyden. ...

When I heard my voice for the first time [on air] ... it was painful. I just think, "Oh my God," I was, first of all, over enunciating so emphatically. I was so tense. Forgive me, I sounded so gay. Not that that's a bad thing. Not that I try not to sound gay these days. This is a few years later, the first time I was guest hosting Morning Edition, I actually got a postcard in the mail that said, "Dear Ari, Please, butch up. I find a daily dose of your personality annoying." ... I love that postcard so much. It has sat framed on my desk for more than a decade now. I just treasure it.

Audio interview produced and edited by: Sam Briger and Susan Nyakundi. Audio interview adapted for NPR.org by: Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey.

Copyright 2023 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.