Two Abenaki First Nations are continuing to call for Vermont institutions not to work with state-recognized tribes, and to reconsider the process that led to the state recognizing those groups as Abenaki tribes.

Those nations — Odanak and Wôlinak — are receiving a mixed response.

Their requests come amid several news organizations — including Vermont Public — releasing investigations into contested claims about the legitimacy of Vermont’s state-recognized tribes. Vermont Public’s reporting was published last fall as a three-part series called “Recognized” within the podcast Brave Little State.

In the “Recognized” series, Vermont Public reported that Odanak and Wôlinak have asked for an investigation into Vermont’s state recognition process, which lawmakers approved in 2010. Last month, the First Nations also sent a letter to Vermont educators, requesting that they stop using information sourced from state-recognized tribes.

Odanak and Wôlinak say the four state-recognized groups are “unrelated to the real Abenaki.” And they say this causes “potential harm to the genuine heritage and cultural identity” of Abenaki peoples.

Vermont’s state-recognized tribes, meanwhile, dispute these claims. They say the First Nations are trying to erase their presence, and that they’d rather coexist.

To explain what’s going on, Vermont Public’s Elodie Reed spoke to The Frequency podcast host Mitch Wertlieb. This interview was produced for the ear. We highly recommend listening to the audio. We’ve also provided a transcript, which has been edited for length and clarity.

Mitch Wertlieb: So in the “Recognized,” series, you looked into Odanak and Wôlinak First Nations’ claims about the state recognition process, right?

Elodie Reed: Yes. And one of the things we found was, Vermont’s state recognition process did not require groups to document their descendancy from historical Indigenous peoples.

And that is counter to how Indigenous peoples generally identify, at least according to the National Congress of American Indians and the United Nations.

It’s important to note that Indigenous Nations are self-governing political bodies that have maintained historical continuity and sovereignty since they first interacted with settlers. And that it is up to each Indigenous Nation to collectively determine who belongs and who does not.

We also reported that almost all the core families making up the Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi — which is by far the largest state-recognized tribe — have not or cannot demonstrate their Abenaki ancestry. That’s according to reports by state and federal authorities and a recent peer-reviewed paper.

Mitch Wertlieb: Well, what do Vermont’s state-recognized tribes say?

Elodie Reed: They say they’re being unfairly scrutinized. And they defend the rigor of the state recognition process, saying they did submit genealogical documentation establishing “kinship and ancestry.” But Vermont’s public record law explicitly says genealogical documents provided for state recognition won’t be made public. And so we can’t verify what they contain, or to whom they establish kinship and ancestry.

And again — Vermont’s state recognition criteria is looser than what is required for federal recognition and also for enrollment in many Indigenous Nations.

Mitch Wertlieb: So I'm wondering: How are lawmakers thinking about all of this?

Elodie Reed: So I went to the Statehouse this month on a day when representatives from state-recognized tribes were in the building to talk to lawmakers.

And at one point, they were recognized on the House floor by Craftsbury Rep. Katherine Sims and greeted by a round of applause.

Katherine Sims: From our state-recognized tribes: Chief Brenda Gagne, Chief Don Stevens, Chief Roger Sheehan, Linda Sheehan and Rich Holschuh. I hope the members will join them — in welcoming them to the Statehouse.

House Speaker Jill Krowinski: Will the guest of the member from Craftsbury please rise and be recognized.

Elodie Reed: In recent years, Sims has received an award from the Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs, and she currently facilitates the Native Caucus. In response to Odanak and Wôlinak First Nations’ request for Vermont authorities to investigate state recognition, Sims says that issue is in the past.

Katherine Sims: Continue to feel like the Legislature had its process. And you know, that the committees of jurisdiction did their due diligence. And that also feels like a kind of internal Indigenous conversation and hope that the different tribes can find a way to come together and have difficult conversations and find a way forward.

Elodie Reed: As for whether the Legislature might re-examine its role in state recognition, Sims had this to say:

Katherine Sims: Yeah, I think that's a question for the folks who chair those committees about — and you know, who were there at the time.

Mitch Wertlieb: So were you able to find any of those lawmakers, who were there at the time of state recognition?

Elodie Reed: Yeah. So one lawmaker who meets that criteria is Waterbury Rep. Tom Stevens. He says he has no plans to revisit the process.

Tom Stevens: We won't be looking at redoing our state recognition, we're pretty happy with where it is right now… The recognition process that we formed here was to try to benefit individuals who identified as Indigenous. And what was important to us was that the government wasn't saying that they're Indigenous, we've — we have a long 400-plus-year history of telling people who they are, especially Indigenous people.

Elodie Reed: And he pushed back against concerns from Odanak and Wôlinak First Nations that the state recognition process appears to have elevated and benefited groups of people who have not or cannot demonstrate their Abenaki ancestry — which is, again, a norm among Indigenous Nations.

Tom Stevens: I will disagree that we need to require descendancy or blood quantum in order to determine indigeneity in this state. That's not our place. It's a supremacist and racist way of looking at things, that from — from the state system. Individuals, individual tribes are free to make those decisions amongst themselves. And I think our legislation allows for that.

Elodie Reed: Stevens says he’s hearing from people both affiliated with state-recognized tribes, and not. And he says that while he is sympathetic to anybody feeling that harm has been done — including the Abenaki First Nations — he says their accusations have cut deep.

Tom Stevens: I'm disappointed in the conversation that's happened. I'm disappointed in the — this strong desire on the parts of many to attack people in ways that are harmful. That's what I see. ... But I don't think that — I don't think turning over the legislation is gonna help.

Mitch Wertlieb: Did you speak with lawmakers who took a different view?

Elodie Reed: Yeah. I spoke with Chittenden County Sen. Kesha Ram Hinsdale, who was also involved with Vermont’s state recognition legislation as a young state representative over a decade ago.

She says it has always been important to her for Vermont to acknowledge the history, dignity and political rights of Indigenous peoples in this region. And that the process was contentious back then much as it is now.

Kesha Ram Hinsdale: I was one of the only people of color in the building, so probably one of the only people who was a bit inoculated when I was called racist for, you know, challenging a very white-presenting group of people on whether or not we should simply write their indigeneity into law.

Elodie Reed: Ram Hinsdale says the original state recognition bill didn’t name specific groups.

Kesha Ram Hinsdale: I hoped that we would have a process led by Indigenous leaders that included scholarly experts that have an archaeological and genealogical background that would help us ensure integrity in the process.

Elodie Reed: But she says that’s not what happened, and says she’s personally apologized to Odanak First Nation for her role in the state recognition process.

Kesha Ram Hinsdale: When I apologized, it was — it was for my zeal in trying to create a process that gave people that dignity of recognition while not having national tribal experts and nationally-recognized Indigenous groups at the table.

Elodie Reed: And moving forward, she says she will continue meeting with Odanak First Nation. And she wants to take the path that does the least harm to Abenaki peoples’ reputation and heritage.

Kesha Ram Hinsdale: That all said, those most impacted are pretty clear that the biggest harm has already occurred, that they feel erased by some of our work. And we have to listen to that.

Mitch Wertlieb: Did any other lawmakers share the views of Senator Ram Hinsdale?

Elodie Reed: Yes. I also spoke with Sen. Thomas Chittenden — he also represents Chittenden County. And he says he’s been in touch with Odanak First Nation as well.

He says he’s still learning about the issue.

Thomas Chittenden: We will not benefit if we keep any of this conversation in the shadows, in the closet, in the dark. We should openly discuss and — and look at our history and our roots.

Elodie Reed: One thing Chittenden says he was concerned to learn about was a Vermont residency requirement for testimony in Senate committee hearings in 2011 and 2012, when state recognition of different groups was being debated. This effectively excluded most Odanak perspectives.

Thomas Chittenden: I think that is a glaring oversight when it comes to recognizing that those individuals that have claims to this land that precede those boundaries of the state of Vermont — and that's what we're really talking about here, is unceded land.

Elodie Reed: The House committee hearings don’t appear to have had a similar residency requirement at that time — but no witnesses affiliated with Odanak are listed in those hearing records.

Chittenden says he wants Vermont’s year-old Truth and Reconciliation Commission to get involved, and to examine the concerns raised by Odanak and Wôlinak First Nations over who Vermont has recognized as Abenaki.

Mitch Wertlieb: OK, so lawmakers are having what sounds like mixed responses to the First Nations’ request to investigate state recognition.

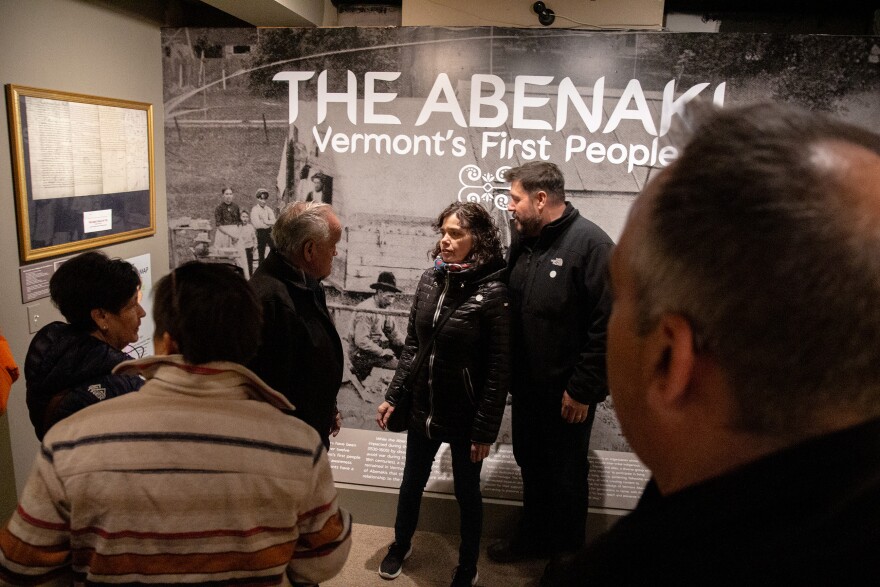

In the meantime, if you walk through say, the Vermont Statehouse, or the Burlington airport, or in various libraries and museums, you will see displays about Abenaki heritage and culture. These are set up namely by members of state-recognized tribes — and according to your reporting, Elodie, the Abenaki First Nations take issue with that.

Last month, I understand Odanak and Wôlinak sent a letter to about 50 people in Vermont’s museum, library and education fields. What are they asking for?

Elodie Reed: The Abenaki First Nations say that if it is educators’ intention to work with the people who have preserved Abenaki culture and language through 400 years of colonization — Odanak and Wôlinak First Nations are those people.

They say their nations have survived centuries of war, dispossession and removal from lands that became the U.S. and Vermont, and that while an international border cut their traditional territory in two, Abenaki peoples have continued to travel, live and trade in their ancestral lands.

And the Abenaki First Nations invited educators to meet with them.

Daniel Nolett: If you want Abenaki material, stories, history and stuff, then you should call on us instead of calling on them.

Elodie Reed: That’s Odanak First Nation’s band council manager Daniel Nolett. He says several interested people have gotten back after the letter went out.

Daniel Nolett: I think we're gaining ground, every week, every month, you know, every small steps that we do.

Mitch Wertlieb: Is that your sense, too, that the First Nations are gaining ground in Vermont?

Elodie Reed: Well, I’d say they’re succeeding in getting more people to discuss this issue out in the open — though not all. About a week after the letter to educators went out in early February, I attended a meeting of the Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs, which is charged by law to develop policies and programs to benefit Native Americans in Vermont.

And during that meeting, a Vermont Agency of Education official said that the agency could help connect educators with the curriculum that state-recognized tribes are building about Abenaki peoples. That curriculum would be voluntary, but it comes at a time when the state is updating its education standards to be more inclusive, culturally responsive and anti-discriminatory.

The Agency of Education later said in a written statement to Vermont Public that while it was aware of the issues raised by Odanak and Wôlinak, it also respects the state recognition process.

Mitch Wertlieb: OK, so it seems like the Agency of Education isn’t exactly getting into this issue. But you said some people are?

Elodie Reed: Yes. The co-coordinators of the statewide Education Justice Coalition of Vermont — which has been actively organizing around this state education standards update — met with the Commission on Native American Affairs in mid-March. They were there to acknowledge they are struggling with this controversy surrounding Vermont’s state-recognized tribes, and whether they are Indigenous.

Here’s co-coordinator Kayla Loving.

Kayla Loving: Like, I definitely see both sides of you know, like, telling you that your — your identity is like, not real. And then also someone saying, like, “You’re stealing my culture.”

Elodie Reed: And here’s co-coordinator Alyssa Chen.

Alyssa Chen: And it makes us uncertain of like, who do we work with? What do we uplift? When, like, our kind of values guide us to think about, we need to listen to stories that are untold, we need to teach the truth. It's like, we don't know what the truth is in this moment.

Elodie Reed: Chen added that the concerns raised by Odanak and Wôlinak First Nations — and also, those of Vermont state-recognized tribes — shouldn’t be ignored.

Mitch Wertlieb: And how are state-recognized tribes responding?

Elodie Reed: Abenaki Alliance, the group that represents the four state-recognized tribes, didn’t respond to my request for comment.

But Rich Holschuh, the chair of the Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs, told me people are hurting, and he feels there’s a lack of comprehension about the issue in Vermont. During that meeting with Chen and Loving, Holschuh said he didn’t understand how this issue is being perceived as a two-sided conflict.

Rich Holschuh: It's not a conflict, it's aggression. And there is no inclusivity allowed there, they're dismissive… So rather than — rather than that embracing of all of the stories, which we should all seek, we've got contention. Instead of inclusion.

Elodie Reed: And he’s not alone. Here’s Jeff Benay, who also sits on the Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs.

Jeff Benay: How is it that you see the Vermont Abenaki as the aggressors? How does that philosophically, or just — just how does that ring true for you?...I find it abhorrent …that Odanak you know, claims to be the victim.

Mitch Wertlieb: OK, maybe we should just zoom out here a bit, Elodie? Why are two Abenaki First Nations headquartered in Canada so concerned about what’s happening in Vermont?

Elodie Reed: So, we have to remember that present-day Vermont, along with New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Maine and Quebec, are part of traditional Abenaki homelands, homelands that Odanak and Wôlinak say they never ceded after they were displaced by European settlers. There’s also plenty of documentation showing that Abenaki peoples maintained a visible presence here after colonization. Most of their 3,000 or so citizens don’t live on those reserves in Quebec.

And it bears repeating that this is actually not a new issue. Indigenous scholars point out that white Americans have been imitating Indigenous people throughout U.S. history.

Mitch Wertlieb: And it’s also not new for the Abenaki Nations, especially Odanak, to be in touch with the groups that became state-recognized tribes, right?

Elodie Reed: Right. They were actually initially supportive of the groups that became state-recognized tribes. Their denouncement of those groups over lack of genealogical and historical documentation then came in 2003. Several Odanak citizens were active in protesting Vermont’s state recognition process a little more than a decade ago, and Odanak’s government issued another denouncement in 2019.

Mitch Wertlieb: OK, and then I remember there was a pretty contentious event at the University of Vermont in 2022.

Elodie Reed: Yes, and that is what marks the increasing presence of Odanak officials speaking publicly in Vermont. Jacques Watso is an elected official for Odanak. He put it to me like this:

Jacques Watso: We still have our collective memory that those are our ancestral territories, and we are caretakers of those territories.

Elodie Reed: And Watso says it’s his duty as an elected official to defend traditional Abenaki territory — and particularly in Vermont, because of how well organized state-recognized groups are.

Mitch Wertlieb: And is it only elected Abenaki officials who feel this way?

Elodie Reed: No, there are Abenaki First Nation citizens who are active in this defense as well. Denise Watso, an Odanak citizen who lives in New York, protested Vermont’s state recognition process.

Denise Watso: It's painful to even go to Vermont, you know, because of what has transpired for over 20-some-odd years.

Elodie Reed: She says going through that experience has made her upset, and even nervous, to be back in the state. But she did spend time here last spring, at another UVM event attended by a number of citizens from Odanak and other Indigenous Nations.

Denise Watso: When I got there and I got to this environment, and I had all these Indigenous people and our allies … it gave me hope and power.

Elodie Reed: After that event, she says, she and a couple others walked down the hill to the lake. It was a warm, sunny day.

Denise Watso: Went out, walked down and started drumming, and it was a beautiful experience. And I think that's more that, what has to happen. Because as we're drumming and singing the traditional songs, we’re generating our ancestors’ power, I think, to guide us and to give them their voice back.

Have questions, comments or tips? Send us a message.