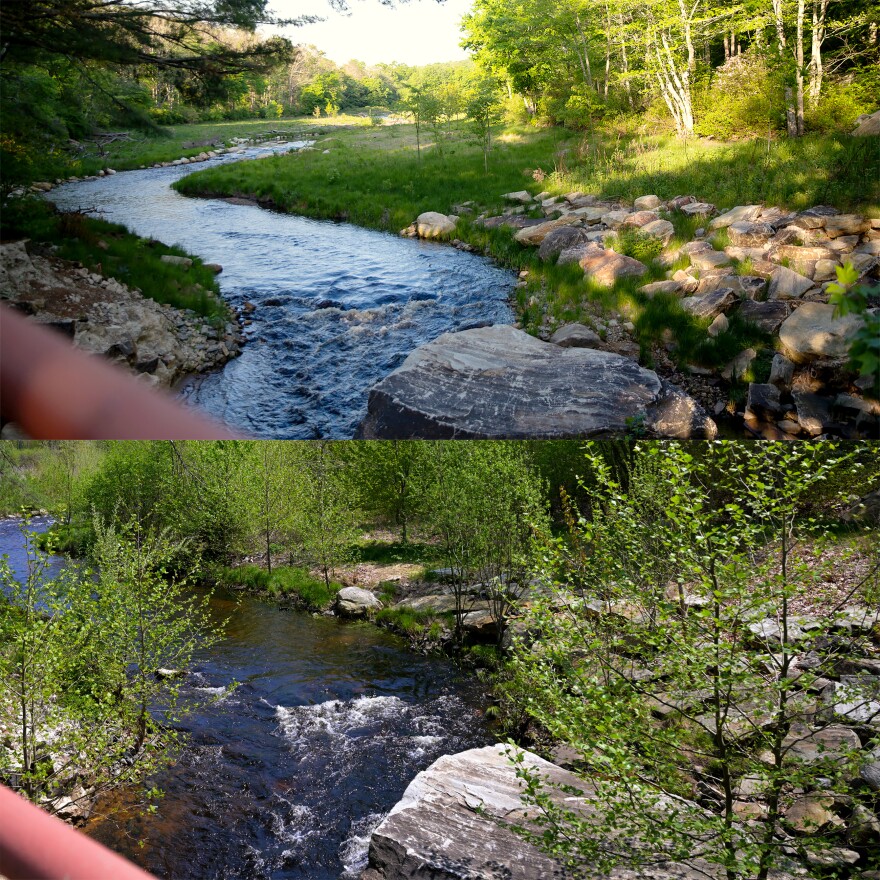

The east branch of the Eightmile River is flowing fast, clear and cool underneath a bridge along Salem Road in Lyme. It’s a perfect May afternoon – sunny and warm – and all around are new trees, bushes and plants, filling out a large half circle of land that bends in the river.

But for decades, the river didn’t flow here. Instead, the whole area sat submerged underneath water trapped by the 80-year-old Ed Bills Pond dam.

In 2015, that dam was removed. And in eight years, the landscape has changed dramatically.

But in the land of Steady Habits, getting people to support dam removal can sometimes be hard, said Amy Singler, director of river restoration at American Rivers. It’s “changing a landscape from what people are used to,” she said.

Singler worked in 2015 on the project to remove Ed Bills dam. And when the dam first came out, the area looked pretty muddy.

“Pretty much like a moonscape,” Singler said. “It's hard to envision what that's going to look like afterwards.”

But it doesn’t take nature long to reclaim the river banks. “We did very little planting,” Singler said. “There's a native seed bed underneath that really springs up.”

Why dams are removed in CT

It’s estimated Connecticut has at least 4,000 dams. Many of them are privately owned. Decades ago, many were originally built for farms, small industrial uses or recreational enjoyment.

“We don’t have that many natural ponds and lakes in New England,” Singler said. “So, if you are passing a pond, chances are it involves a dam.”

But dams can be expensive to maintain. Because of that, some owners, like the owners of the Ed Bills Dam, choose to remove them, which itself is costly.

The Ed Bills Dam removal was primarily funded through grants from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Long Island Sound Futures Fund, with additional support from Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) and private fundraising.

(BOTTOM) The Dam Removal project finished, at the Eightmile River in Lyme, Connecticut on May 10, 2023 (Dave Wurtzel)

Restoring connectivity

Emily Hadzopulos is the freshwater restoration project manager for the Nature Conservancy. Freshwater systems are like vascular systems in human bodies, she said, and building a dam is like “clogging an artery.”

Removing a dam helps migratory fish and freshwater fish, which are often, themselves, food sources for other species.

“Connectivity increases the accessibility to cold water streams,” Hadzopulos said, which is increasingly important due to climate change. Fish, she said, need connected rivers to find new water sources during droughts, find cooler waters during heatwaves and find the right places to breed.

Singler said fish and any freshwater species “need that connected river system the same way that we need roads … to get where we're going.”

Dams don’t just harm fish. They can be an infrastructure risk, too.

What’s the best way to ensure a dam doesn’t fail? Get rid of it.

Removing an old dam is a guarantee against any future dam failure. “I had heard an engineer once say that the best day of a dam's life is the day that it's put in,” Singler said.

Dam failures are a growing concern among environmentalists and engineers as the state’s dams get older and the region’s weather gets more severe due to a changing climate.

“We tend to see a lot drier summers now, and go longer times between rainfall. But when we get rainfall, it tends to be more intense,” Holly Drinkuth, director of river and estuary conservation for The Nature Conservancy in Connecticut, said.

You’re not just removing a threat of a dam failure, you’re also allowing the landscape to once again be ready to handle heavy downpours, Hadzopulos said.

“You're creating more floodplain,” she said. “So then, the water has more room to spread out.”

While the east branch of the Eightmile River is now completely dam free, there is one remaining dam downstream, the Moulson Pond Dam, which has had a fish ladder since 1998.