What does it take to make a Puerto Rican holiday dinner here in Connecticut compared to on the island? That’s what Connecticut Public’s Rachel Iacovone and El Nuevo Día’s Itzel Rivera hoped to find in the grocery aisles in Connecticut and Puerto Rico.

Iacovone went to a Hartford location of CTown Supermarkets, a Latino grocery chain in the Northeast U.S. Meanwhile, Rivera shopped at a location of Econo in Guaynabo, a suburb of San Juan. Econo is one of the biggest and oldest grocery chains in Puerto Rico — and as the two found, one of the cheapest.

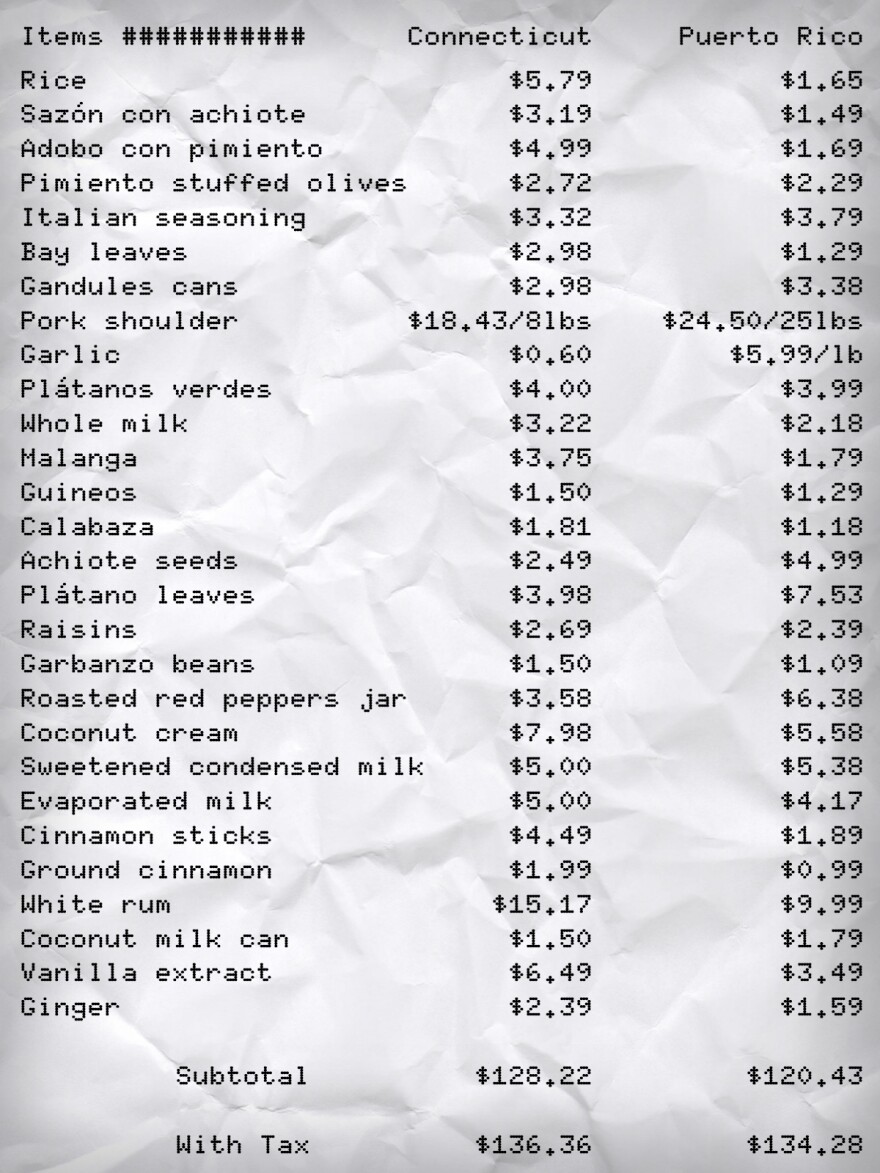

The list

Iacovone and Rivera were shopping for traditional Christmas dishes, including arroz con gandules (rice and pigeon peas), tostones (fried plantains), pernil (roasted pork), pasteles (kind of like Puerto Rican tamales), arroz con dulce (a thicker rice pudding dessert) and, of course, coquito (affectionately known as Puerto Rico’s eggnog).

The shop

Rivera had assumed that her cart would cost more in Puerto Rico.

“I was expecting everything to be super expensive. And when I got there, I saw that there were lots of Christmas specials already. For example, the rice was cheaper than I thought, and other things, like gandules, were cheaper,” Rivera said. “I think that’s what really surprised me: It was that everything was cheaper than I thought.”

Groceries often do cost more in PR because of a law that’s nearly a century old, according to director of economics at The Budget Lab at Yale Ernie Tedeschi.

“The Jones Act will raise the price of things in Puerto Rico,” he said. “When there are trade tensions or global supply chain disruptions, like we had in the pandemic, Puerto Rico is more vulnerable than a lot of other places to factors that affect that.”

Before he was at Yale, Tedeschi was a chief economist at the White House Council of Economic Advisors under President Joe Biden.

“Certain factors make Puerto Rico higher cost than it could otherwise be, especially when it comes to items around international trade. Obviously, Puerto Rico has to import a lot of what it consumes,” Tedeschi said. “So, for example, the regulations around shipping into Puerto Rico and how it has to be American-flag ships.”

There were some items in Puerto Rico that were significantly cheaper than in Connecticut. Traditional spice blends and tropical produce – like malanga, a root vegetable Boricuas grate for the masa for pasteles — were less than half the price in Puerto Rico.

Tedeschi explained some of why that is. While Puerto Rico has these products locally, Connecticut has to import them in this age of tariffs.

“Imports coming in from other countries, those are the ones that are going to show the effects first. A lot of times, retailers have pre-tariff inventory that they're burning through first, so customers don't see a tariff effect right away,” Tedeschi said. “That's not applicable to fresh produce. You work your way through it very, very quickly. Otherwise, of course, it goes bad, and then, you have to re-import, restock your fresh produce.”

The numbers

In the end, the local versus imported goods mostly evened out the two carts’ costs. The subtotals in Connecticut and Puerto Rico had just an $8 difference, but then, there are the taxes.

In Connecticut, the sales tax rate is 6.35%. In Puerto Rico, it’s a whopping 11.5%.

“Here in Puerto Rico, everything is getting really expensive,” Rivera said. “The cost of living is higher than what we gain.”

Boricuas make more in Connecticut than on the island, but most are working minimum-wage jobs. In Connecticut, a Puerto Rican household makes on average $48,656, according to data from UConn’s Center for Puerto Rican Studies. In Puerto Rico, the median household income is $25,621, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2023 American Community Survey.

That same data shows the overall median household income in Connecticut that year was $91,665.

So, Puerto Ricans on the island are paying about the same for ingredients. But since they are making around a quarter of what Nutmeggers do, they are paying a higher proportion of their income on food.