Black men in Connecticut fought for American independence while bound by a system that denied their own freedom — a contradiction that still shapes how the nation remembers its founding.

“I think that plays a part when you have what’s happening this year, you know, the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and all these celebrations,” historian and genealogist John Mills said. “It creates a scenario where you have African Americans and people of color that just don’t feel associated with this celebration. But if these stories had been told all along, they would be much more aligned.”

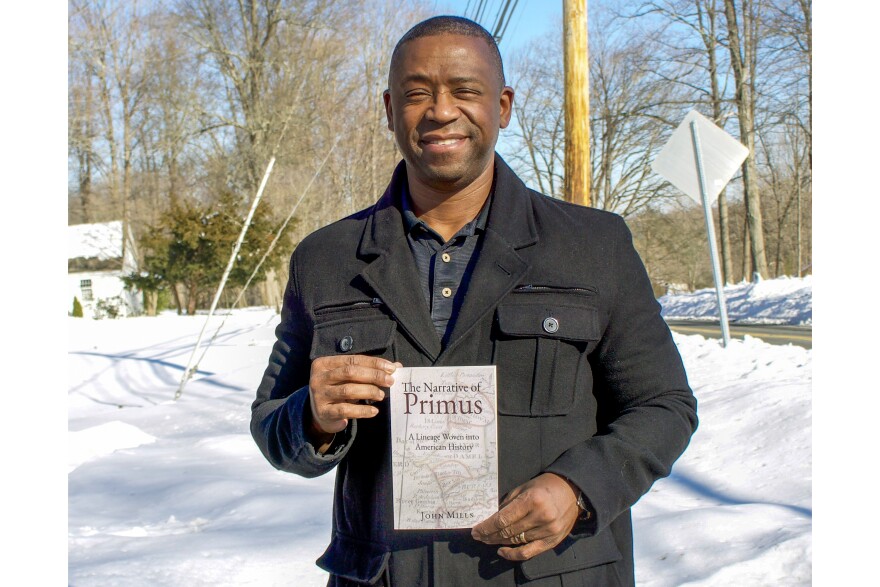

Mills’ new book, The Narrative of Primus, traces one Connecticut family across generations to illuminate the broader Black experience during the Revolutionary War era.

A family story rooted in the nation’s founding

Mills’ research centers on Primus, a child captured in Africa and enslaved in Connecticut, and on the generations that followed. He said the family’s history reflects how Black lives intersected with pivotal moments in American history.

“Primus’s second great grandson fought in the Civil War,” Mills said. “[Primus’ son] Job fought in the Revolutionary War. He was at the Battle of Trenton with George Washington.”

The family’s experiences reveal shifting policies and uneasy realities. During the Revolutionary War, George Washington initially barred Black men — enslaved or free — from serving. That stance changed when the British began accepting them, Mills said, underscoring how Black service often followed national need, rather than national recognition.

“There’s a legacy of this scenario where black men are kind of not being given the appropriate reverence to the same ability to fight for our nation, and then they’re utilized when there’s like an issue that the country needs them,” he said.

Fighting for liberty while enslaved

Job’s story captures the contradiction at the heart of the Revolutionary War. He fought for independence, but remained enslaved after returning home.

“He’s fighting the Revolutionary War. He’s enslaved, and he gets back. He’s still enslaved,” Mills said. “After he fought, he’s still enslaved, and the enslaver is not agreeing to free him.”

A young Norwich resident intervened, purchasing Job’s freedom and recording the justification in local land records. Even then, freedom carried a cost. Mills said Job later used his military wages to secure his wife’s release.

“They were patriots at a time where they’re being treated poorly, and they’re having to pay for freedom twice, for the country and then for their families monetarily,” he said.

Service shaped by constraint — and determination

Black participation in the Revolutionary War took multiple forms. Some men fought in place of enslavers. Others enlisted with broader hopes for equality.

“What I see most commonly is that these men were fighting to build equity and equality amongst them and people that look like them,” Mills said. “They were trying to prove that we are just as capable as white Americans.”

He described a stark contrast in motivation. White patriots fought within a framework that affirmed their status, while Black patriots fought to challenge a system that denied their worth.

“Black Americans had this ‘I’m being told I’m not as valuable. But watch this,’” Mills said.

Recognition still unfolding

As the nation approaches the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, Mills said a fuller telling of the Revolutionary era requires bringing long-overlooked Black experiences into the center of the story. He said broader recognition can reshape how communities understand both the nation’s founding and their place within it.

“I think that plays a part when you have what’s happening this year, you know, the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and all these celebrations,” Mills said. “It creates a scenario where you have African Americans and people of color that just don’t feel associated with this celebration. But if these stories had been told all along, they would be much more aligned.”